In her book, Invisible Women, Caroline Criado Perez exposes the data bias in a world “designed for men”. One of the book’s most important chapters addresses the biases against women in the medical world, specifically through medical gaslighting. Medical gaslighting is a set of behaviours displayed by doctors and other medical professionals, that make the patient question whether they are actually experiencing their symptoms. For example, blaming your physical symptoms on mental illness, or making you feel like you’re catastrophising or being dramatic. Essentially, medical gaslighting is when a doctor dismisses your symptoms and worries as unimportant, exaggerated, and/or not serious enough to require further investigation.

Chapter ten of Invisible Women, The Drugs Don’t Work, opens with an anecdote about a sixteen-year-old woman who had been experiencing painful, bloody bowel movements for two years, until it got so bad that she decided it was time to see a doctor. She was rushed to the emergency room, where a doctor asked her if she could be pregnant – no, she said. She hadn’t had sex; besides, the pain was in her bowel.

“The next thing I knew, a large, cold metal speculum was crammed in my vagina. It hurt so badly I sat up and screamed and the nurse had to push me back down and hold me there while the doctor confirmed that I indeed, was not pregnant.”

The young woman was then discharged with “nothing but an overpriced aspirin and the advice to rest for a day”. Over the next decade she sought help, and eventually she was diagnosed irritable bowel syndrome and ulcerative colitis. For years, she had been repeatedly told that all of this was in her head, and it wasn’t until she was twenty-six that she finally had a colonoscopy that diagnosed her condition (Invisible Women, p 195-6).

This infuriating account reminded me of two similar incidents that happened to me in the last few years.

It’s Just Anxiety, Dear

Some four or five years ago, I was on a commuting on a train when I started having very odd symptoms. Every minute, I would have an episode of what I can only describe as all of my senses short-circuiting which lasted for about twenty seconds and came back every few minutes. I couldn’t see, I couldn’t hear, I was confused every time it happened. To begin with, I thought maybe it was vertigo or a migraine aura, but my vision wasn’t the only sense affected and my head was not hurting. I started to feel quite worried, so I asked the people on the train to call an ambulance for me.

At the hospital, I remember having blood tests and an ECG (a test to see how the heart is doing). No brain scan though. After many hours of waiting, I was seen by a doctor who concluded that it was all… anxiety. (Yes, female doctors can gaslight too). She talked to me condescendingly, and even gave me a patronising hug and pep talk about looking after my mental health. After the hospital visit, my symptoms lasted a whole week.

I went to my local GP to get a different opinion, who ran a few more tests and it turned out that my problem has been physical after all. He suspected I had a few simultaneous infections going on in my body. He prescribed me antibiotics and eventually I started feeling better. To this day, I’m still not sure if the diagnosis was right. I never even had a brain scan, and with symptoms like that and a concussion in my medical history, was I wrong to expect them to take me more seriously? Why didn’t they?

To refer back to Invisible Women, it’s possible that the way women are socialised to “downplay their own status” and behave in a friendly and approachable way, may prevent from effective diagnosis. However, a lot of the time even when a woman says exactly what’s going on and how much it affects her quality of life or safety, she is still dismissed. Invisible Women tells another story of a woman, Kathy, who was told by four medical professionals that her problems were all in her head, which later turned out to be a potentially life-threatening case of uterine fibroids which required surgery. Another woman, Rachel, was also told her pain was imaginary. She was consistently told that there was nothing wrong with her, until finally, years later she was diagnosed with endometriosis (p 223-4). Endometriosis is an incurable condition where tissue similar to the lining of the uterus is found on other organs. It can cause extreme pain (to the point of fainting and not being able to walk), and it takes an average of eight years to diagnose. Sadly, it is a condition I am too familiar with.

This Will Only Hurt a Lot – Endometriosis, PCOS, and Intrauterine Systems (IUS)

Four years ago I wanted to get an IUS (also known as the hormonal coil). I still do. I wanted something I could just forget about, something that wouldn’t make my periods worse, and something that didn’t involve a lot of hormones because I’m prone to blood clotting (due to a genetic disorder, a story for another time). An IUS seemed to fit my needs, so about four years ago I tried to have it inserted for the first time. A year later, I tried to have it done again. Then a couple of years later I tried it again. And again, and probably one more time. In total, it must have taken five or six tries before I just gave up because of the insane pain that nobody warned me about.

Every time, the doctor (or another medical professional) who was going to insert the coil told me that most women experience “some discomfort” on insertion.

Some discomfort? I have never experienced a worse pain in my life – I felt like my insides were being ripped apart. I nearly passed out each time I tried to get it done, but every time I would reach a point where I thought “this is not worth the pain”. Some discomfort my arse.

No one told me that it could be excruciating for some women, and when I asked to be sedated to have it done, it was refused because that’s “not how we do this procedure in the UK”.

Similarly, when I was diagnosed abroad with PCOS (polycystic ovary syndrome), the doctors in the UK were refusing to officially diagnose me because I wasn’t overweight (which is a typical symptom of PCOS but all women with the syndrome are overweight). But did they offer to scan my ovaries and check? Of course not. They refused that too. What was I supposed to do? Have cancer so they take me seriously?

Apparently so.

It took an actual cancer scare to finally get me referred to a gynaecologist. A blood test for ovarian cancer markers came back with a concerning result, so I was rushed to the hospital (by rushed I mean it took two weeks to get seen by a doctor), I had scans done and was diagnosed with PCOS and endometriosis. Thankfully, no cancer. It turns out endometriosis can also cause a spike in the ovarian cancer marker test.

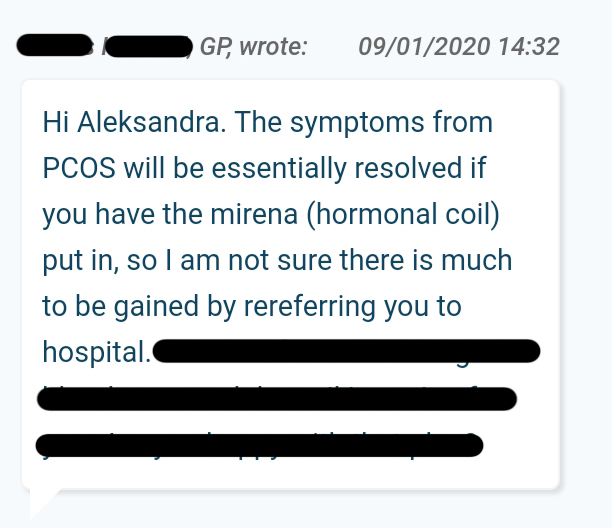

The oncologist I saw there told me to ask my GP for a referral to Dr Gynaecologist to discuss my treatment options for PCOS . Even then, my GP told me that he didn’t think there was much to be gained from the referral since having a coil put in could resolve my symptoms.

Why don’t I just shut up and do what he (not a specialist) says, since he knows better than a gynaecologist (a specialist).

Why Does Medical Gaslighting Happen?

Why do women have to be in a potentially life-threatening situation to be taken seriously? To have further tests done? To be believed?

I thought, maybe medical gaslighting is happening because the NHS is under so much pressure, and they can’t afford better care. Although it could be a contributing factor, women are being dismissed and disbelieved by doctors around the whole world. This is not a UK-specific issue. It goes deeper than that.

“The result of this deeply male-dominated culture is that the male experience, the male perspective, has come to be seen as universal, while the female experience–that of half the global population, after all–is seen as, well, niche.” Because of this male-centric world we live in, research into the female body and illness is put to the side. There is an infuriating lack of funding for medical research relating to women’s conditions, decided by panels of men, which leads to a massive data gap that explains why a lot of conditions that affect women (or those that affect men too but show differently in women) are misunderstood and misdiagnosed. This, along with the tendency to see women as hysterical (which is still pervasive in medicine), leads to women being dismissed by medical professionals, and to their suffering being reduced to a figment of their imagination.

Personally, I have decided to stop feeling bad for talking to doctors when I’m feeling unwell. I am not imagining things. I am going to challenge a dismissive GP whenever I encounter one, and I encourage others to do the same. Only by challenging medical gaslighting and raising awareness about this issue, will we move closer towards fairer and safer treatment of women.

Do you have a story about being dismissed or gaslighted by a medical professional? Tell us in the comments below, or DM us on Instagram and we will publish your stories on our social media to spread awareness!

Disclaimer: All of the above can be relevant to any gender, I simply focused on women because they tend to be dismissed more than men by medical professionals.

This article ended up being half a personal account, and half a letter of praise to Invisible Women. Please read it. You won’t regret it.

#metoo 30 years of gaslighting for 3 medical issues funny thing is when it turns out you were right and they were wrong no one is sorry and they still try to gaslight me now so I avoid drs coz they lie and when they are proved wrong that’s when the cover up starts oh she is depressed let’s drug her. ” Take your soma like a good girl and shut up and go away “

I went to the doctor in excruciating pain, could barely walk, couldn’t do up my jeans. .. She diagnosed me with gas. I knew there was something seriously wrong and I was flabbergasted, took a moment to gather myself and went into the doctors lunch room and said please see me again… there’s something wrong with me. She started asking me if I had problems with flatmates, stress. So I left dizzy and bought the gas pills and staggered home. A few hours later I called a taxi to take me to the hospital. In the taxi I struggled for air grabbing at it and went unconscious. Momentarily, I came to and my foot was dragging on the floor and I was slumped being wheeled through a corridor. A few hours later I awoke in intensive care. I had a ruptured ectopic pregnancy, was operated on, had some blood transfusions and recovered. The doctor told me I was very lucky to have survived. ..